What is risk? Project risk is defined by the Project Management Institute as, “an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on a project’s objectives.” Risks to a project are maintained in a risk register, with a trigger and response mechanism. Risk management tools allow uncertainty to be addressed by identifying and generating metrics, parameterizing, prioritizing, and developing responses, and tracking risk. These activities may be difficult to track without project management tools and techniques, documentation, and information systems.

The risk process is a multistep process consisting of identifying, understanding, mitigating, assigning a trigger event, and having a risk response plan. In a project, identified risks are put in a risk register, understood, mitigated, assigned a trigger event and a risk response plan.

While this article discusses negative risks and how to reduce their impact, remember that there are positive risks as well. There’s a risk that are positive, like getting a grant. It’s uncertain, but you do what you can to enhance it by writing a good proposal and sending it in on time. A speaking engagement might lead to a new opportunity. Enhance that with good preparation, a polished presentation, and being ready to take advantage of anything that arises. You want to mitigate negative risks, but enhance positive risks.

Let’s step through this in the context of owning a house. There are many identified negative risks to a house, theft, earthquake, flood, fire, etc. We will use a single item in our risk plan to go through the various items:

- Identification: We could have a house fire.

- Understanding: A house fire could be large or small. It can have a variety of causes, including unintentional or intentional. It could start from poor maintenance or faulty construction. (This is qualifying and quantifying risk, determining impact and probability).

- Mitigation: We’re pretty sure we don’t want a house fire. We take steps to reduce the impact of a fire. We keep fire extinguishers in the kitchen and garage. We keep important documents and mementos in a fire-resistant safe. We have a system that automatically calls the fire department. We buy house insurance. We have a fire escape plan. We also take steps to reduce the probability of a fire. We follow fire department recommendations on creating a “fire-safe” home, for example not storing oily rags. We make sure wiring is good and don’t overload outlets. We are careful when cooking over open flame on our gas range, never wearing lose clothing or overheating oils. We decide we love our propane grill, so we keep that, but we move it further away from the house.

- Trigger event: FIRE! (The risk is realized in project-management parlance.)

- Risk response plan: If the fire is small, use an extinguisher. If the fire is large, follow fire escape plan the house. The smoke alarm automatically notifies the fire department whether we are home or not, regardless of the size of fire. After the event, damaged is assessed and we call the insurance company and repair experts.

Understanding a risk is the process of qualifying and quantifying. If it is expensive to fix, does that change our understanding? No, it doesn’t – but it might change how much we choose to mitigate or what our risk response plan looks like. For example, you identify the knees on your jeans are thin and could rip. By looking closer, you understand it’s likely. You mitigate by choosing to do nothing and accept the risk, since patching looks silly and is an expensive use of time. Trigger event, the jeans rip. Risk response, you put on a different pair from the closet and get rid of the ten-year-old jeans.

Realize that some requirements can change greatly and without warning – this can dramatically change a risk profile in a very short amount of time. If a risk area has a particularly large impact, mitigation should be considered. Whether that mitigation is considered is dependent on the cost of mitigation vs. the cost of the realized risk.

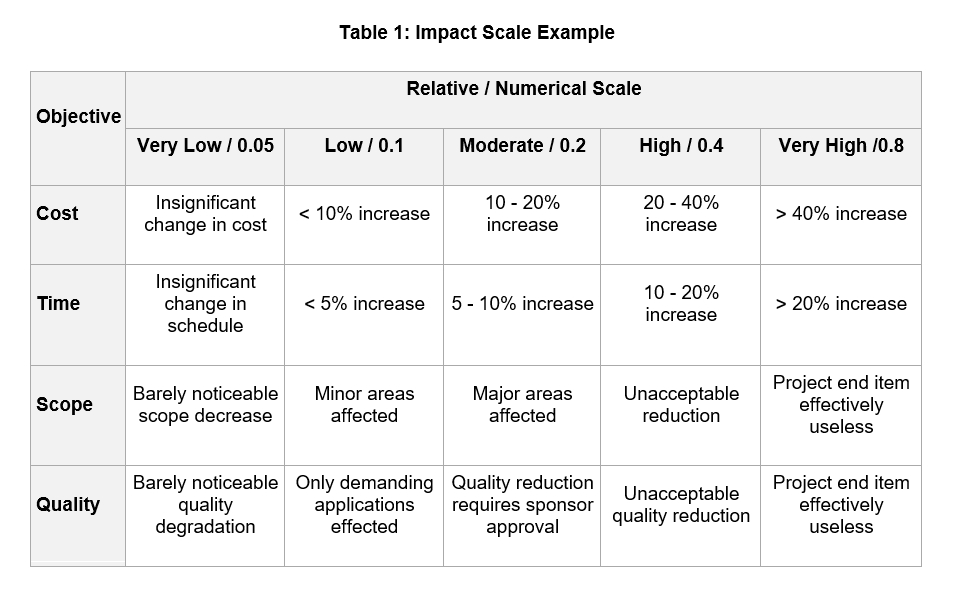

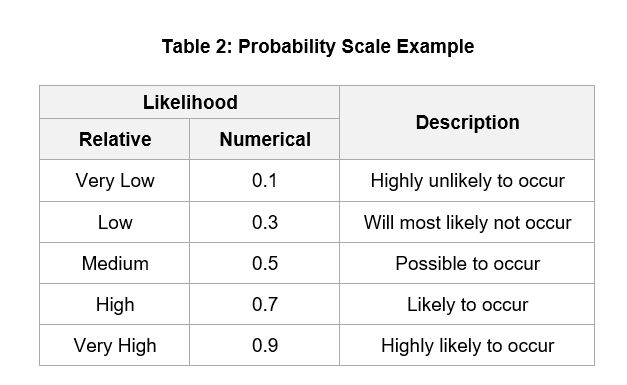

The largest task is understanding risk, qualifying and quantifying it. Generally, risk is viewed across two dimensions – impact and probability. The impact, “does it matter”, of the risk event is viewed as very low, low, medium, high, or very high. The probability, “is it likely” of occurrence is viewed the same way. Impact multiplied by probability results in a simplified risk score. Depending on the risk score, different responses can be modeled. Below is the scoring system from the Project Management Body of Knowledge 5th Edition (PMBOK v5) in two tables:

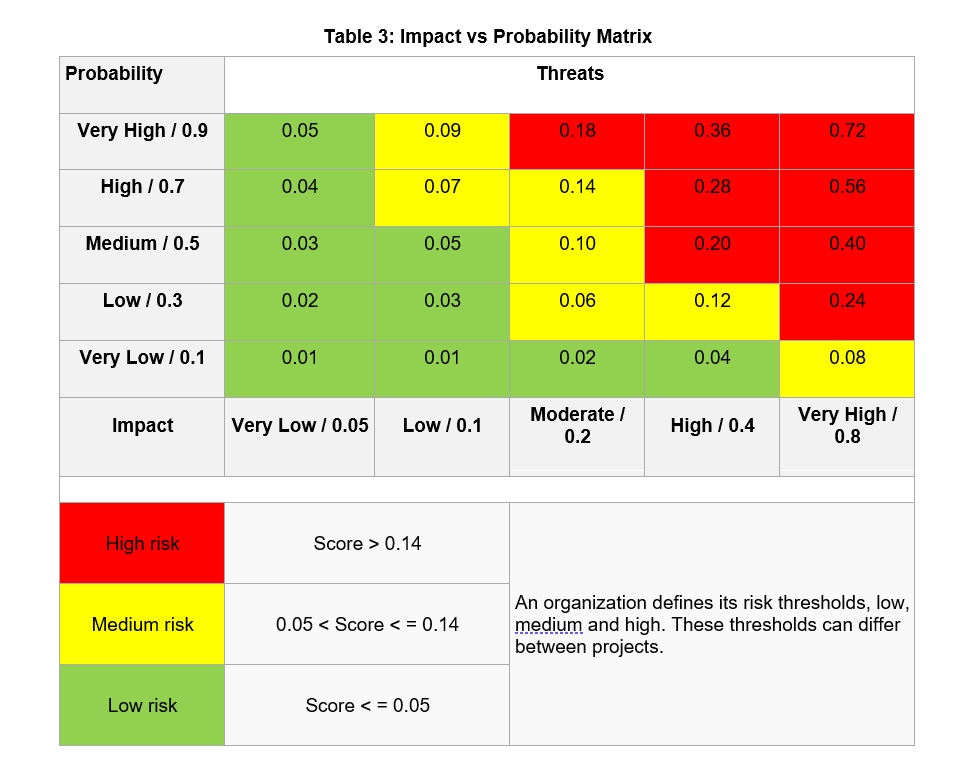

Multiplying impact and probability results in a risk score, categorized as high, medium or low. This is showing in Table 3, below. Based on the risk score, determination can be made on how to address the risk.

A quick demonstration of an assessment. A meteorite could land on my house. What is the impact? Well, most meteorites are fairly small, under 25 milligrams. Larger are very rare, but possible. Let’s call that low impact. What’s the probability? The earth is fairly large, most of it water. The chances of a meteorite hitting my house instead of anyplace else is very low. Low Impact (.1) x Very Low Probability (.1) = Low Risk (.01).

With a language to describe risk, it is possible to apply it to other contexts. Breakdowns of impact (how broad and/or deep is the effect) and probably (how often and how likely). A papercut has low impact, but 99% likelihood of getting 1000 per second would be high risk. This kind of analysis determines “severity” of a bug in software, a “crash-on-every boot in every scenario” being both high impact and high probability, making it a high risk to product success.

In classic project management, risks are identified, qualified/quantified, mitigated (ignore a risk, insure it away, work to min/max probability, work to min/max impact – there are positive risks as well as negative risks), assigned a trigger event (what causes a risk response) and a planned risk response. This material becomes part of a project risk register, the “if this, then that” plan.

This rubric can provide a better way of discussing risk. Risk process provides a predictable, data driven way to speak about risk, and why mitigation or risk response is important/not-important. If a mitigation or a risk response is a lot of work, disruptive, or expensive, that factors into that part of the plan – not the discussion of the risk itself.